The rovers got stuck in other celestial bodies. But, I team of engineers solved the problem.

Source: TechXplore

When a multimillion-dollar extraterrestrial vehicle gets stuck in soft sand or gravel—as did the Mars rover Spirit in 2009—Earth-based engineers take over like a virtual tow truck, issuing a series of commands that move its wheels or reverse its course in a delicate, time-consuming effort to free it and continue its exploratory mission.

While Spirit remained permanently stuck, in the future, better terrain testing right here on terra firma could help avert these celestial crises.

Using computer simulations, University of Wisconsin–Madison mechanical engineers have uncovered a flaw in how rovers are tested on Earth. That error leads to overly optimistic conclusions about how rovers will behave once they’re deployed on extraterrestrial missions.

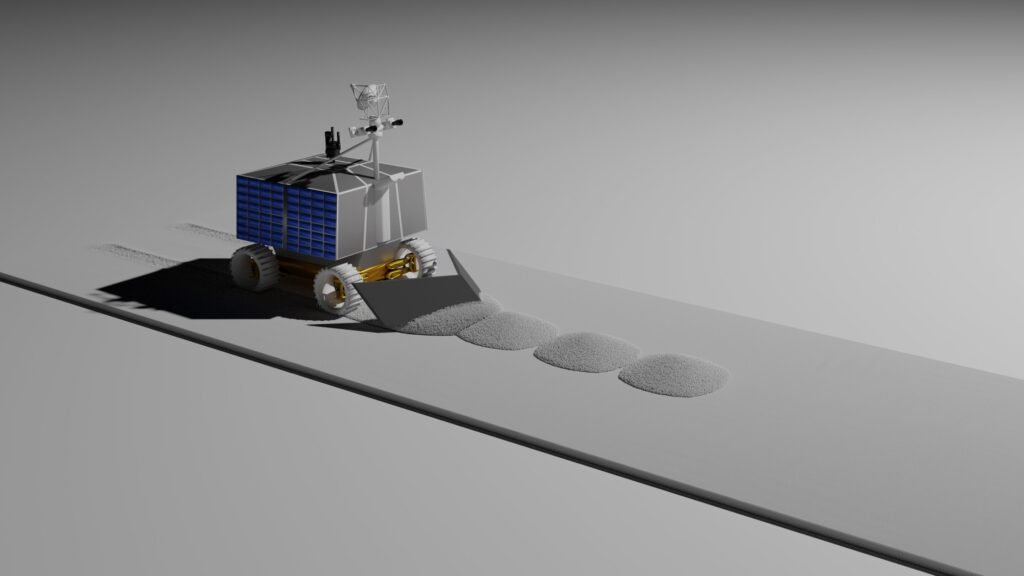

An important element in preparing for these missions is an accurate understanding of how a rover will traverse extraterrestrial surfaces in low gravity to prevent it from getting stuck in soft terrain or rocky areas.

On the moon, the gravitational pull is six times weaker than on Earth. For decades, researchers testing rovers have accounted for that difference in gravity by creating a prototype that is a sixth of the mass of the actual rover. They test these lightweight rovers in deserts, observing how it moves across sand to gain insights into how it would perform on the moon.

It turns out, however, that this standard testing approach overlooked a seemingly inconsequential detail: the pull of Earth’s gravity on the desert sand.

Through simulation, Dan Negrut, a professor of mechanical engineering at UW–Madison, and his collaborators determined that Earth’s gravity pulls down on sand much more strongly than the gravity on Mars or the moon does. On Earth, sand is more rigid and supportive—reducing the likelihood it will shift under a vehicle’s wheels. But the moon’s surface is “fluffier” and therefore shifts more easily—meaning rovers have less traction, which can hinder their mobility.

The team recently detailed its findings in the Journal of Field Robotics.

The researchers’ discovery resulted from their work on a NASA-funded project to simulate the VIPER rover, which had been planned for a lunar mission. The team leveraged Project Chrono, an open-source physics simulation engine developed at UW–Madison in collaboration with scientists from Italy. This software allows researchers to quickly and accurately model complex mechanical systems—like full-size rovers operating on “squishy” sand or soil surfaces.

While simulating the VIPER rover, they noticed discrepancies between the Earth-based test results and their simulations of the rover’s mobility on the moon. Digging deeper with Chrono simulations revealed the testing flaw.

The benefits of this research also extend well beyond NASA and space travel. For applications on Earth, Chrono has been used by hundreds of organizations to better understand complex mechanical systems—from precision mechanical watches to U.S. Army trucks and tanks operating in off-road conditions.

Chrono is free and publicly available for unfettered use worldwide, but the UW–Madison team puts in significant ongoing work to develop and maintain the software and provide user support.

Co-authors on the paper include Wei Hu of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Pei Li of UW-Madison, Arno Rogg and Alexander Schepelmann of NASA, Samuel Chandler of ProtoInnovations, LLC, and Ken Kamrin of MIT.