The tungsten carbide-cobalt is one of the hardest industrial materials, for which was developed an aditive manufacturing technique.

This material can cut metal, concrete and rocks. Only sapphire and diamond are harder, in addition to have great resistance to heat and weariness.

Source: SciTechDaily

Its standout hardness is also its biggest manufacturing headache. Once this material is formed, it resists shaping so strongly that production can become slow, wasteful, and costly compared with the amount of usable product that comes out at the end.

That problem matters because tungsten carbide-cobalt (WC-Co) cemented carbides are relied on anywhere abrasion and heavy loads quickly destroy ordinary metals, including cutting and construction tools. Today, manufacturers typically turn to powder metallurgy, where WC and Co powders are pressed and then sintered under high pressure and high heat to create a solid cemented carbide component.

The drawback is efficiency. Powder metallurgy can deliver excellent hardness and durability, but it often consumes more expensive material than the final part actually requires, and yield suffers. The study explores a different route by pairing additive manufacturing (AM, also commonly known as 3D printing) with hot-wire laser irradiation, aiming to place cemented carbide only where it is needed while keeping performance intact and reducing waste and cost.

The study was published in the International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials.

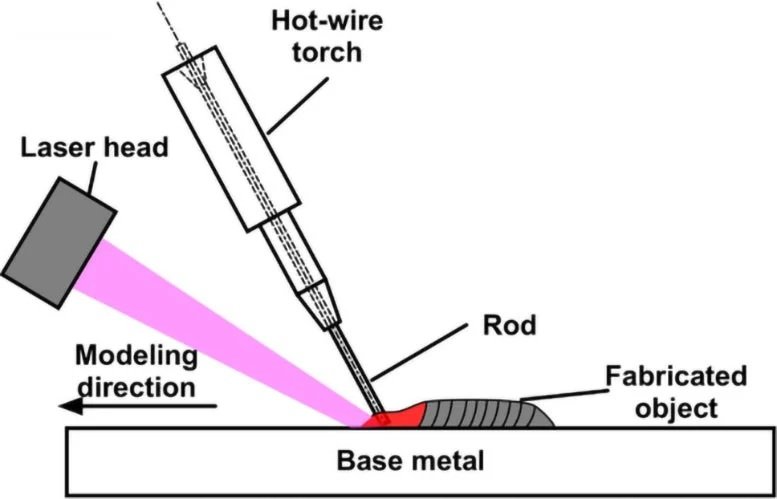

Instead of treating cemented carbide like a block that must be carved down, the researchers test whether it can be built up more selectively using AM. Their key tool is hot-wire laser irradiation (also called laser hot-wire welding), which combines a laser beam with a preheated filler wire. Preheating the wire helps boost the deposition rate (how much of the filler metal is added) and improves process efficiency by reducing how much energy the laser must supply during deposition.

They evaluate two ways to apply this idea. In one approach, the cemented carbide rod moves at the front of the build while the laser irradiates the top of the rod. In the other, the laser leads and targets the region between the bottom of the cemented carbide rod and the base material (iron). In both setups, the goal is to soften the metals rather than fully melt them, a choice intended to help form cemented carbide while limiting the extreme thermal conditions that can damage hard, brittle materials during processing.

“Cemented carbides are extremely hard materials used for cutting tool edges and similar applications, but they are made from very expensive raw materials such as tungsten and cobalt, making reduction of material usage highly desirable. By using additive manufacturing, cemented carbide can be deposited only where it is needed, thereby reducing material consumption,” said corresponding author Keita Marumoto, assistant professor at Hiroshima University’s Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering.

The results demonstrated this method to be effective in maintaining the hardness and mechanical integrity of conventionally manufactured WC-Co cemented carbides, achieving a base material with hardness of over 1400 HV (a unit representing resistance to penetration), without introducing any defects or decomposition.

Producing the cemented carbide molds without defects does appear possible, which is the main goal of this study, though some results vary.

For example, the rod-leading method appears to lead to the decomposition of WC on the upper part of the build, leading to defects in the final product. The laser leading method also had issues maintaining the hardness necessary for success. A nickel alloy-based middle layer was added, and that, along with maintenance and monitoring of temperatures (above the melting point for cobalt, below the temperature of grain growth) lead to a cemented carbide produced via AM without sacrificing material hardness.

The promising results are a springboard for improving upon their work. Researchers would like to see their work here progress to manage the issue of cracking, as well as form more complex shapes.